Private equity firms have found a new way to make money that raises ethical concerns: investing in asbestos liabilities.

In recent years, this practice has been gaining popularity among Wall Street firms. It consists of taking on the financial risks associated with asbestos-related illnesses and deaths in exchange for substantial payouts from manufacturers.

Asbestos was once a widely used material for construction work due to its heat resistance and durability. However, it left a devastating legacy. The material’s microscopic fibers can be easily inhaled and they are known to be a cause of lung cancer and other similar debilitating conditions that affect the respiratory system.

The harmful effects of asbestos were discovered by scientists in the 1920s but it wasn’t until 40 years later that workers managed to win the first few lawsuits and got paid by companies who intentionally used the material due to its low cost, despite knowing the risks that it posed to their health.

Also read: 10 Biggest Real Estate Companies in the US by Market Cap

In 1970, the United States Congress classified asbestos as a hazardous air pollutant and companies progressively abstained from using the material. However, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) waited until 2024 to prohibit its ongoing use, meaning that thousands of facilities in the United States are still made of asbestos and continue to intoxicate people.

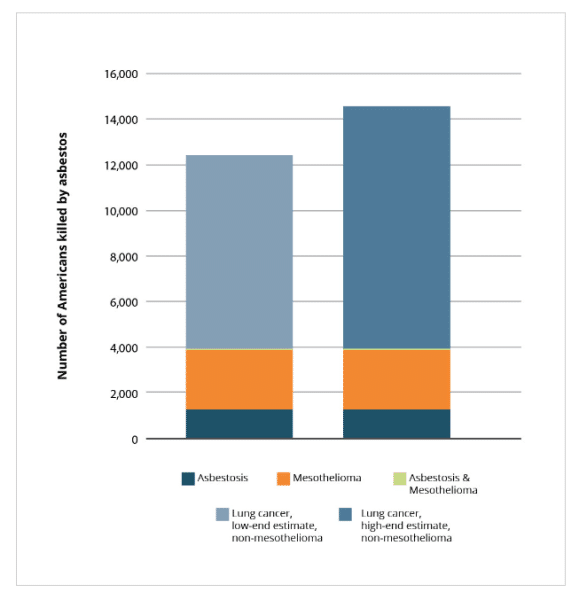

The impact of asbestos exposure is nothing short of mind-blowing. Over 40,000 deaths nationwide are linked to asbestos annually. Thousands of lawsuits have been filed by individuals seeking compensation and more than 150 companies have filed for bankruptcy due to asbestos-related claims. On average, settlements can range from $1 to $1.4 million.

Unfortunately, private equity firms are now buying up these liabilities and are fighting to pay out victims as little as possible, only making their problems worse.

Warren Buffett Pioneered Asbestos Liability Investments

Warren Buffett’s firm, Berkshire Hathaway, pioneered this kind of investment. However, as a result of Berkshire’s exposure to the insurance sector, both ethical and regulatory issues – alongside a handful of lawsuits – pushed back against the company and its aggressive buying of this type of security.

Private equity firms with lower moral standards were eager to jump in and they started buying what Berkshire left on the table.

“Because for all practical purposes Berkshire Hathaway was first into the sector and with scale, it was able to charge [manufacturers] what today would today might be considered a fortune. Now, sales of asbestos liabilities have become a competitive market, with many private equity firms aiming to take a slice of the pie,” Stephen Hoke, an attorney with experience in liability sales, told Jacobin.

How does the scheme work? Typically, manufacturers create a subsidiary company that takes up the asbestos liability. This is the company that will bear the legal costs and impact of the active lawsuits.

They pour millions of dollars into the company and fight the legal claims in courts with the plaintiffs. If the latter gets compensated, the money within the subsidiary is paid out and the company typically files for bankruptcy but leaves its parent out of the mess. However, if the lawsuit is won, the subsidiary keeps the money.

Creating this subsidiary means that the parent can escape the liability, even though it was at fault for hurting its victims, often leaving them uncompensated.

What Berkshire – and now PE firms – do is buy the exposed subsidiary and get involved in the legal proceeding. Warren Buffett’s company was accused of dragging its feet in court, delaying legal proceedings, and appealing endlessly to avoid paying plaintiffs. In the process, they invested the money and earned interest or dividends on it.

Also read: Warren Buffet’s Investment Checklist – The Secret to His Success?

Naturally, this is a pretty cruel practice as the legal battle becomes torturous for the plaintiffs who are often suffering from severe medical issues. In far too many cases, the victim died during the battle and the legal proceedings would be closed.

The result: Berkshire and PE firms keep the money that should have been paid to these victims. Since these settlements are often worth millions if not billions of dollars – for class-action lawsuits – they can bring in sizable profits by engaging in this practice.

Several recent transactions highlight the growing trend. In 2021, Delticus Group, part of Warburg Pincus, acquired InTelCo Management LLC from ITT Inc. for $398 million. In 2023, Delticus received $189 million to acquire asbestos liabilities from Ingersoll Rand. In 2022, Global Risk Capital LLC partnered with Premia Holdings to acquire SPX Technologies’ asbestos liabilities for $139 million.

A prominent example from 2021 involves the acquisition of InTelCo Management LLC, a subsidiary used by the manufacturing company ITT to bear the cost of its asbestos liabilities. InTelCo was bought by a unit of the global PE firm Warburg Pincus for $398 million.

Last month, this same unit bought another asbestos liability-carrying vehicle of the well-known manufacturing giant Ingersoll Rand for $189 million.

Private equity firms view these transactions as financial instruments with several appealing characteristics. They can generate stable cash flows from investing their pool of cash, they offer reliable yields, and the end result of the investment can be tightly controlled by managing the legal proceedings that these subsidiaries face.

According to a February report by the consulting firm Milliman, there has been a noticeable uptick in these types of deals in recent years.

Lack of Oversight Creates “Wild West” Scenario and PE Firms Know It

The lack of regulatory oversight of these investments is a cause of concern among legal experts and people who advocate for workers’ rights. According to Michael Shepard, an attorney who represents victims of asbestos exposure in Boston, investors have managed to get their hands on “a deep well of cash” and are able to “handle it the way they want” without any regulatory supervision.

Even though Berkshire Hathaway had to take a step back due to regulatory and legal concerns associated with insurance industry malpractices like “bad faith”, private equity firms are not subject to these rules.

Regulators in key states like New York and California have commented that they have not received any complaints regarding this practice and confirmed that these dealings would effectively fall outside their jurisdiction.

Also read: How Billionaires Are Made in 2024 – The Tremendous Rise of the Asset Management Industry

PE firms engage in certain ethically questionable practices like creating a subsidiary that declares bankruptcy after the legal proceeding. As a result, plaintiffs are forced to keep fighting their case in court but now to get a piece of the bankrupted entity as their legal claim is just one in an often long list of creditors.

“The companies that exposed people to asbestos are finding ways to evade having to pay for the harms that they have caused down the road. Victims moving forward may not have any recourse to pursue for their injuries because of what is taking place now,” Shepard stressed.

Regulators May Soon Step Amid the Ethical Issues Raised by “Asbestos Investing”

The same practice is being applied to companies with liabilities associated with other toxic chemicals like polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are also known as “forever chemicals”.

Similar techniques are being adopted by PE firms involving the acquisition of the subsidiaries that are bearing the brunt of the legal claims associated with exposure to these chemicals. By 2020, insurance claims related to these substances had reportedly produced over $90 billion in payouts.

In the end, if the practice isn’t done away with, companies who have caused tremendous harm to innocent people as well as the environment will continue to get away with a slap on the wrist while their victims toil in long legal battles.

Even though the acquisition of these liabilities is entirely legal, it does fall into a regulatory gray area that could soon face higher levels of scrutiny and oversight. The potential abuses from PE firms to drag legal proceedings and do everything they can to avoid plaintiffs from being compensated for what they suffer opens up the door for regulators to step in.

Meanwhile, as these Wall Street firms continue to profit from acquiring toxic liabilities, victims of asbestos exposure and other hazardous chemicals face a double injustice. First, they suffer from the health consequences of being exposed to these substances. Then, they must navigate a complex legal process controlled by profit-driven entities.

Shepard summarizes the ethical dilemma as follows: “[These investors have] found a way to make money off of victims, and that’s just wrong.”